Five things we liked in group stage, and five things we never want to see again.

Two teams dropped out of MLS is Back before it even started, and there were times in group stage when it looked like NYCFC had made it three. But things weren’t all bad—outside of the disastrous start against Orlando, Ronny Deila’s men have been the better team more often than not—so we went around the table to talk about what’s working and what’s not.

Justin Egan

What to Build On: Although I still think that this tournament should not have been held, it does seem that since FC Dallas and Nashville were sent home, and despite some questionable safety practices, Covid-19 has been contained so far in the Disney bubble. All of the positive tests have come from faulty testing or players who contracted the virus before entering the bubble. That’s good news. But the fact that MLS and the NBA are burning through thousands of tests every week and getting results in a couple hours while the public health system is struggling to provide regular people access to timely testing is morally reprehensible.

What to Learn From: The 3-5-2 that Ronny Deila brought out for the first half hour of Orlando made me so mad I think my hairline receded a couple of inches. I can’t decide which was worse, the shape or the names on the teamsheet. The lineup featured seven players whose best position is in defense or defensive midfield, plus two attackers and whatever Jesús Medina is these days. Ronny’s selection of Gudi over Keaton Parks makes me wonder if he really did finally get around to watching NYCFC’s games from last year. When Maxi Moralez is out, Keaton is the only midfielder with the passing skills to link defensive and offensive phases in transition. He may not be a No. 10, but neither is Gudi. The formation, which inexplicably flipped the traditional 3-5-2 midfield triangle and left NYCFC’s buildup in shambles, was also questionable. What was the point of going three at the back against Oscar Pareja’s generic 4-2-3-1? Whatever it was, it didn’t work, and the team played better after changing shape at the water break.

John Muller

What to Build On: Coming into this tournament I still wasn’t sure what James Sands is, and the way Ronny Deila used him in group stage didn’t seem designed to clear that up. Sands started as a center back in a back four against Philadelphia, a right center back in a back three against Orlando, and a midfielder playing sometimes behind, sometimes ahead of Alex Ring against Inter Miami. There was a moment in the Miami game where he carried an intercepted clearance out to the wing, put the moves on the defender, and set up a Medina cross. There was a moment in the mess against Orlando when I remember typing in the chat “jimmy sands shooting from the six yard box everything is normal everything is fine.” But the performance that stuck with me was his lockdown shift against Philadelphia, when Sands’ stolidity looked like the perfect complement to Callens’ more adventurous play in a center back pair. More of that, please.

What to Learn From: The Orlando City goat rodeo aside, Ronny seems like a pretty reasonable guy. Time will tell how his vision of a simpler, more structured NYCFC will shape up, but he’s earned the benefit of the doubt so far by explaining himself plainly and learning from mistakes. And yet one mistake just won’t go away: Jesús Medina has appeared in all eight competitive matches under Deila, starting six of them. Which, look, the first few games? I get it. You’ve got this high-dollar hole in your roster, the kid’s still youngish, he’s got some skills, maybe all he needs is a little time and trust to be the talent he looked like he was becoming before his sudden implosion two years ago. But even after Deila conceded that Medina’s not a winger and brought him into a more natural attacking mid role, Medina has kept being Medina, drifting in and out of games (mostly out), getting bullied off the ball any time a defender looks at him in a way that hurts his feelings, and just generally being the worst player on the team. Yeah, it sucks that City Football Group won’t buy the team three functioning DPs, but don’t force the issue. There’s talent on that bench. Use it.

Chris Campbell

What to Build On: Ronny Deila still has work to do learning the squad, who his best options are, and what combinations do and don’t work (see above re Medina, Jesús). But it appears in his quarantine-induced film study, he noticed how productive the Heber-Taty partnership was in 2019. The two South American strikers may not have brought their finishing boots to Orlando, but they’ve combined for 2.15 expected goals on 20 total shots in the two matches they’ve played together. It’s still up for debate how they best fit together, and Ronny is feeling his way through that as he tried Taty as a box-crashing left winger against Philly and a second striker against Orlando. When the partnership was broken in the third game due to a mysterious Héber injury, NYCFC only mustered 0.71 xG and Taty didn’t get a shot on target.

What to Learn From: As Maxi Moralez goes, so goes NYCFC. The last two matches have exposed the roster’s biggest weakness, the absence of a capable attacking midfielder to spell the aging Argentine. With so little turnover from last year’s Eastern Conference-winning squad, there weren’t many holes to fill and you might have thought finding a capable backup for Maxi would have topped David Lee’s agenda. Instead, Ronny’s been stuck between a marshmallow and a soft place trying to patch the No. 10 hole with Jesús Medina or the ghost of Gedion Zelalem. The ugly results speak for themselves.

Kevin Nelson

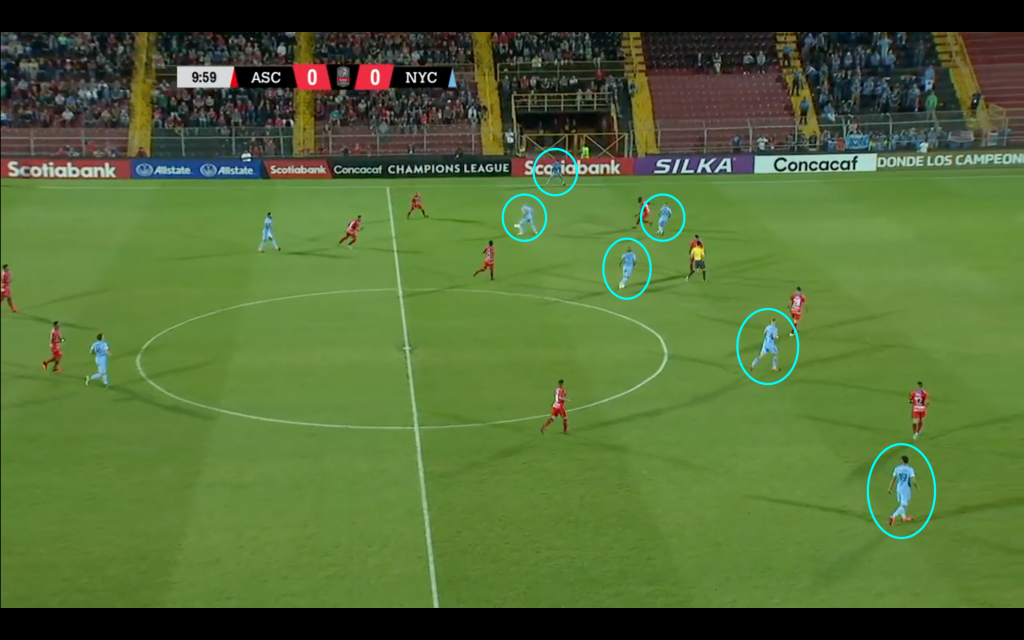

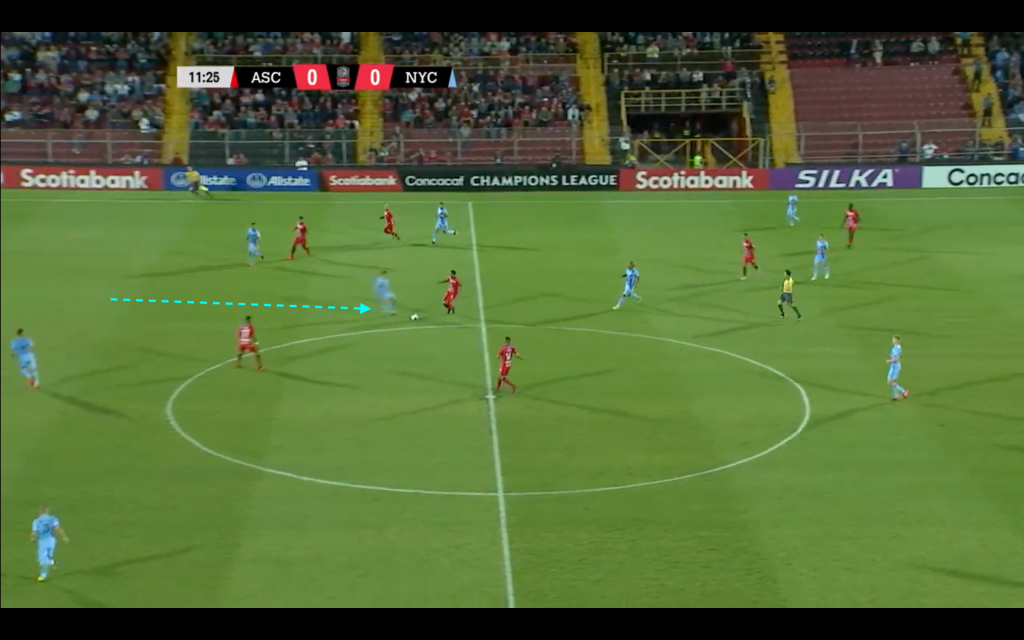

What to Build On: Ronny Deila’s defensive press continued to prioritize funneling possession into the midfield halfspaces in Orlando, a tactic that has proven to be high risk, high reward. It’s allowed NYCFC to launch quick counters off turnovers and attack with a numerical advantage, but the lack of ball pressure on opposing center backs can be invitation to slice through the defense. Inter Miami put together two dangerous buildups in the opening ten minutes when the press was activated, and Deila seemed to have a come to Jesus moment where his defense shifted to cutting off central passing lanes and forcing long balls. It remains to be seen whether the adjustment was evidence of Deila’s tactical acumen, but it’s a promising indicator that he can identify problems and change his plans accordingly.

What to Learn From: Héber is one of the best strikers in MLS at dropping in to link up during the buildout. His movement and connectivity naturally distort opponent defenses, making room for all kinds of creative off ball runs. Unfortunately, NYCFC rarely took advantage of that during group stage, offering poor off ball movement in every stage of the attack. Each time Héber drops in to save the buildup, his only teammates interested in making short runs to offer layoff options are the fullbacks. The wingers, Alexandru Mitriță and Ismael Tajouri-Shradi, like to come short and carry on the dribble instead of looking for runs into the space exposed as Héber pulls a backline apart. And things get even worse when you remove Héber from the equation, as we saw against Inter Miami. Considering this same roster didn’t have this problem last year, it’s not unreasonable to pin some of this on the new coach, though injuries and the general weirdness of the circumstances have probably played a part. Maybe Tajouri-Shradi’s goal against Miami, a rare example of good off ball movement, will remind the team what it’s been missing.

NYCFC Tactics

What to Build On: Like Chris said, NYCFC has a Maxi understudy problem. But hark, the solution is on the bench: the Big Bird himself, Keaton Parks. In the Texan’s limited minutes so far in 2020, he’s been dynamic, looking to switch the field and attack the final third vertically instead of doing Medina’s shiftless sashay. If Maxi’s still not ready to start against Toronto, it’s time to give Keaton the microphone and let that bird sing.

What to Learn From: Taty’s scoring ability is stifled by his current responsibilities (or maybe regression to the mean is real). [Editor’s note: Our writer got sidetracked and the draft ends here. Seems that like Castellanos, who led NYCFC in group stage xG but came away scoreless, The Outfield just can’t finish.] ❧

Image: Henri Rousseau, The Repast of the Lion