Ronny Deila’s fledgling romance with a buildup known as the “lovers’ outing.”

During the group stage of the 2006 World Cup, a Spanish newspaper columnist who’d spent that spring playing soccer in Mexico reported something he’d heard about El Tri’s manager, Ricardo La Volpe. For 30 minutes of every training session La Volpe made his center backs practice advancing the ball over and over, coaching their every pass, every decision, until after hundreds of repetitions defenders and ball fell in love. Led by their captain, Rafa Márquez, Mexico’s back three didn’t just start play. That was the phrase people used for shuffling the ball around the back and then booting it long. La Volpe’s center backs salieron jugando, went out with the play. Como novios. Like lovers.

The column’s author was one Josep Guardiola, who was just two years away from taking charge of FC Barcelona and changing the whole world’s ideas about building from the back. But Pep’s hope to emulate La Volpe’s lovers-going-out buildup had one little hitch. Barcelona didn’t like to waste bodies behind the ball when it could have numbers in midfield instead. That meant lining up in a 4-3-3 instead of a three-back system like La Volpe’s. But during the first phase of Barça’s buildup, a lot of opponents pressed with two forwards, one for each center back. How could Guardiola’s defenders drive the play forward without the numerical superiority they needed to find space?

His solution was to drop his defensive midfielder, Sergio Busquets, between the center backs to form a temporary back three. Two opponents couldn’t mark all of them, which meant at least one center back—or, more dangerously, Busquets in the middle—would be free to bypass the first line of pressure and pick the pass that would get Barcelona out of its defensive third in a controlled, purposeful way. The tactic, meant to approximate the Mexican buildup that Guardiola admired, became known as the salida lavolpiana, the La Volpean going-out.

Twelve years into the Pep revolution it’s become commonplace for any coach who aspires to play possession-based juego de posición (which if you’re going off hiring-day press conferences is pretty much all of them) to turn a center back pair into a back three during certain buildup situations. Sometimes that’s done by nudging one fullback toward the middle, although the evolutionary triumph of attacking fullbacks has produced a generation of overlapping whippets who might not be at their best when hanging around at the back. Sometimes a midfielder drops off to one side of the center backs, like Frenkie de Jong loved to do at Ajax. But the salida lavolpiana is still a classic: a defensive midfielder retreats into the middle of the back line, the center backs split wide, and a two-man press watches helplessly as one unmarked defender or another doesn’t just start the play, he goes out with it.

Ronny Deila is (Perhaps) for Lovers

Like everyone, Ronny Deila says he wants to play attacking, possession-based soccer. Unlike everyone, Deila has a squad that’s talented enough, in MLS terms, to pull it off. They’ve been doing it for years. The way New York City FC lined up for its first competitive game under Deila—a 4-3-3 with inverted wingers, overlapping fullbacks, and ball-playing center backs—has been a favorite for this team ever since Patrick Vieira gave up trying to resurrect the W-M.

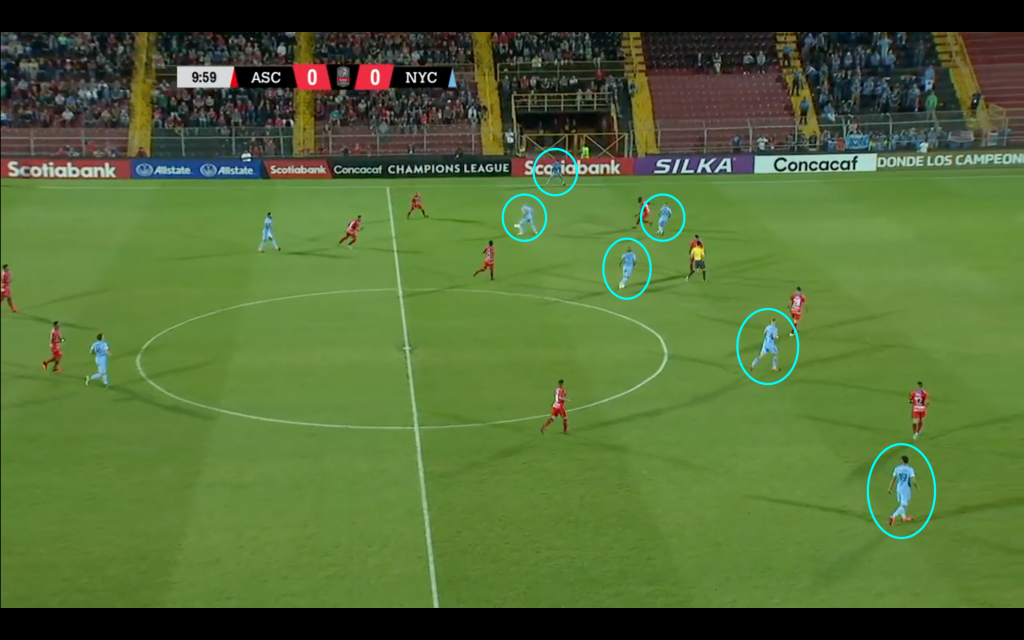

So it wasn’t exactly a surprise in the ninth minute of the CONCACAF Champions League game against San Carlos to see James Sands, whose hybrid position makes him perfect for this kind of thing, relieve pressure on NYCFC’s buildup by dropping from the defensive midfield line into the salida lavolpiana. For a moment he was back in the middle center back role where he got his big break in last spring’s 3-4-3. It felt familiar.

If you looked closely, though, Deila’s first draft of the salida lavolpiana had some peculiar features. Unlike Gregg Berhalter’s version at Columbus, the goal wasn’t for Sands to become a Wil Trapp-style pocket passer but rather to free an outside center back, ideally Alexander Callens, to dribble toward the halfway line and pick a linebreaking pass. Counter to conventional wisdom, one or both of NYCFC’s central midfielders didn’t drop to support the buildup by showing for the ball in the space Sands vacated; instead Alex Ring and Keaton Parks pushed up between the two banks of four in San Carlos’s standard-issue 4-4-2 medium block. And unlike Guardiola, who likes his wingers to provide width, Deila let Alexandru Mitriță and Jesús Medina come inside, sometimes almost colliding with the center mids in the halfspaces. The whole strategy only really lasted about 25 minutes, until NYCFC went up 2-0 and both teams changed their gameplan in response, but it was enough to put tactics nerds in a tizzy.

Here’s how Deila’s buildup worked:

To be clear, CCL Round of 16 ties are still basically preseason games for MLS teams, and analyzing preseason games is, as a rule, a huge waste of time. But this pattern was distinctive enough, and clues about Deila’s style are still scarce enough after weeks of closed-door scrimmages, that it felt worth going to the tape. Will Ronny’s hilariously aggressive salida LOL-piana be a staple of NYCFC’s buildup this season? Does that mean we’re in for a wild year of gunning for 5-4 scorelines? Who wouldn’t have time for that?

The Salida de Ronny

If you skipped past the video in the last section, take a minute to back up and watch it now. It’ll help illustrate the four tactical ideas we’re going to talk about here, the step-by-step objectives that make this buildup interesting.

Relieve Pressure

The whole purpose of the salida lavolpiana is to outnumber the opponent’s press three (or four, counting the goalkeeper) to two. Once the defensive midfielder—here, James Sands—drops between the center backs, somebody’s going to get open.

More often than not against San Carlos, NYCFC would move the ball around until that somebody was Alexander Callens, the Peru international who bosses this team’s buildup. Since 2017, Callens leads NYCFC’s center backs in expected goal chain per 96 minutes (a measure of how likely NYCFC was to score from possessions he participated in) and is second among all MLS players for expected pass score per 100 attempts (a measure of pass quality). Get Callens the ball in space and good things will follow.

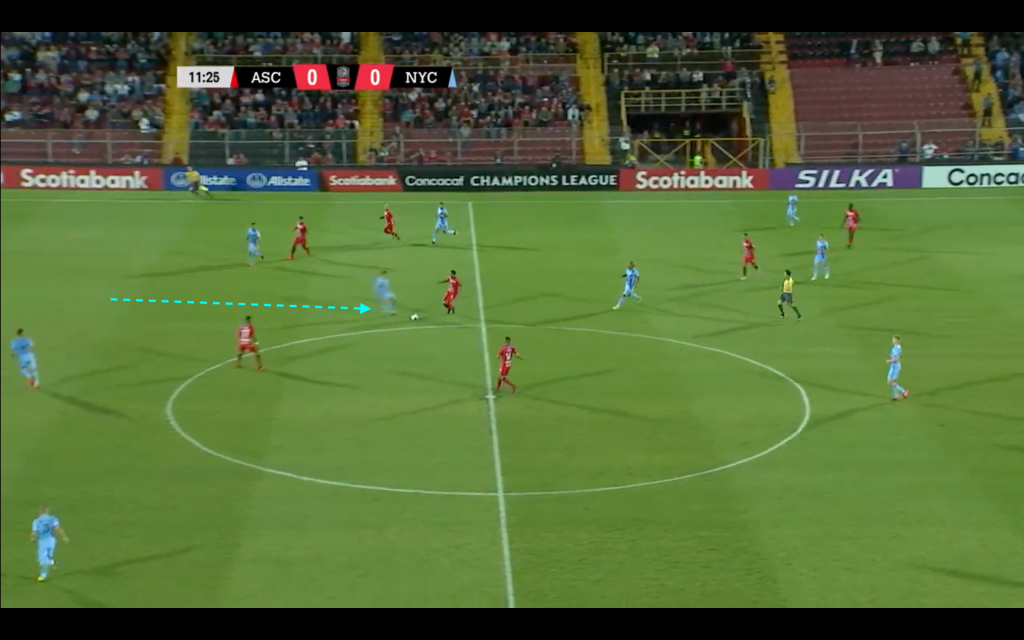

Claim Space, Break Lines

Once you’ve got a player in space, use it. Over and over again Callens would turn upfield with nothing but fifteen or twenty yards of bright green grass in front of him. As San Carlos’s front-line press played catch up, the center back would carry the ball past them and keep going until an opponent left the second line to confront him. As soon as that happened, Callens would pull the trigger on a linebreaking pass through the hole that marker left open. And once you’re between the lines, the defense is in trouble.

In some ways the salida lavolpiana isn’t too different from last year’s 3-4-3, which also spread Callens and Maxime Chanot out to the halfspaces. Getting wide can help the center backs find lanes to make more aggressive passes. According to American Soccer Analysis’s Tiotal Football, Chanot and Callens attempted lower-percentage passes and performed significantly worse against ASA’s expected passing model when playing in a back three in 2019, but those riskier passes were more effective, producing a higher average expected goal value per possession for NYCFC and less xG on opponents’ next possession compared to when NYCFC played four at the back. That’s about what you would expect if the outside center backs were playing more linebreaking passes from their wider positions.

But there are differences from the 3-4-3 too, most notably that Deila’s version of the salida left NYCFC’s defensive midfield line totally empty. There’s no easy passing option—it’s break lines or bust.

Get Numbers Upfield

The reason there’s nobody in the center of the pitch is that Deila pushed both central midfielders upfield between the lines. That’s feasible when the defense is mostly passive, like San Carlos was until NYCFC’s second goal, but it’s a high risk, high reward proposition.

The reward of positioning as many as five attackers between the lines and two more on the wings is obvious: get anyone the ball with room to turn and you’re facing the last four defenders with overwhelming numbers. Even if your first foray fails—a misplaced throughball, a clumsy dribble—you’ve got extra bodies in place to win the ball back in a dangerous spot.

Deila says he wants to improve NYCFC’s counterpress, and it’s true that there’s some room for improvement. Even though the club ranked near the top of the league last season in most high-press metrics, the numbers weren’t quite as dominant as the two years prior. A bottom-heavy buildup and direct attack (part stylistic choice, part function of protecting a lot of leads) meant they weren’t always in position to recover lost balls in the attacking half. Moving more players upfield will help keep opponents off balance.

But there are a couple of not so subtle drawbacks to the ol’ 3-0-7 formation, too. For one thing, that attack can get awfully crowded. Recall that Dome Torrent, who knows Guardiola-style tactics better than just about anybody, sized up this same NYCFC squad and decided it wasn’t suited to a 4-3-3. No extremos puros, wide wingers who could spread the field and beat a fullback up the touchline instead of working inside. Sure enough, Deila’s aggressive buildup sometimes saw the wingers, Mitri and Medina, stepping on the midfielders’ toes in the halfspaces. That proximity can help players improvise short passing combinations, but the suboptimal use of space means you’re going to get caught in awkward positions sometimes.

Which brings us to the second problem with high center mids: yes, they’re in place to challenge for lost balls in the final third, but if a counterattack gets past them you’d better have someone right behind them for a quick tackle or tactical foul. You need your defensive midfielder again.

Reshape and Counterpress

This is where the salida lavolpiana has a natural advantage over a three-back formation: it’s built for flexibility. The defensive midfielder acts like a center back in the buildup, but he’s still a defensive midfielder, and once his services are no longer needed at the back he can charge forward and cut out counters in midfield the way a 4-3-3 is built to do.

Busquets, who’s equally comfortable orchestrating the buildup and snuffing out attacks in the opposing half, was the ideal defensive midfielder for Guardiola’s salida lavolpiana. For Deila’s NYCFC, that two-way player just might be the 19-year-old Sands. In Costa Rica, the homegrown’s dual training as both a center back and a defensive midfielder came in handy as he showed a knack for knowing when to drop into the back line and when to get forward for a well-timed midfield stop.

As a matter of fact, that’s exactly how NYCFC’s first goal of 2020 happened: Sands moved up a line, recovered a loose ball, and two quick passes later Héber was celebrating (when is Héber not celebrating?). The salida lavolpiana was working. The defenders were going out with the play, the midfielders were counterpressing, and Deila was winning the way he said he wanted to win. For the moment, at least, it was easy to love. ❧

Image: Pierre-Auguste Cot, The Storm